WHAT IS OCD?

31 May 2021Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a common mental illness. Earlier it was considered as a rare illness, but studies have now shown that 2-3% of the population have OCD at some point in their life. Though OCD is a common illness, many who suffer from this illness do not seek treatment. It is equally prevalent in both sexes, but more common in boys than in girls if the onset of illness is in childhood and adolescence. Less than 15% develop their illness after age 35 years. The main features of this illness are obsessions and compulsions.

Obsessions are certain thoughts, doubts, images or urges that occur in one’s mind. These are unwanted, repetitive by nature. Most people with OCD realize that obsessions are senseless, irrational, or excessive, but they are unable to ignore or suppress them. They would attempt to resist and control them, but would not succeed. Obsessions cause significant distress and anxiety to the sufferers and as a result cause interference in their day to day functioning.

Compulsions are repetitive acts that the person is driven to carry out in spite of knowing that they are meaningless, unnecessary or excessive. Compulsions are usually in response to obsessions. For example, a person with fear of contamination washes hands repeatedly in order to ensure that his or her hands are clean. The person attempts to resist repeated hand-washing, but gives in to the urge so as to relieve himself or herself of the anxiety or discomfort. Persons with OCD often perform certain acts repeatedly to avoid some dreaded event or to prevent or undo some harm to themselves or others, for instance, touching the floor an even number of times to prevent an accident that one fears might occur to family members. They are aware most of the time that the activity is not connected in a logical or realistic way with what was intended to be achieved, or that it may be clearly excessive (as in the case of hand-washing compulsions), but cannot control them as they reduce anxiety at least transiently.

What are not obsessions?

- The common usage of the word obsession as in, “he is obsessed with music” is not obsession as used in the context of OCD. Here the person indulges in the activity with complete will, has control over it and derives pleasure out of the activity.

- When one is fired from a job or loses someone close to them, it is natural to brood over the event. However, these thoughts are not considered as senseless or irrational, though they may cause some discomfort.

- Similarly, a person appearing for an examination may feel anxious and worry about the results, which could occupy considerable amount of his time. These thoughts, though unwelcome, are under his control and not experienced as senseless. The above experiences are obviously not obsessions.

Some common obsessions:

- Fear of getting dirty, contaminated or infected by persons or things in the environment.

- Blasphemous thoughts.

- Thoughts of harming or killing others or oneself.

- Doubts that a task or assignment has been done poorly or incorrectly.

- Recurring thoughts or images of sexual nature.

- Fear of blurting out obscenities.

- Fear of developing a serious life-threatening illness.

- Preoccupation to have objects arranged in a certain order or position.

Some common compulsions:

- Repeated hand-washing, taking unusually long time to bathe, or cleaning items in the house.

- Ordering or rearranging things in a certain manner.

- Checking locks, electrical outlets, gas knobs, light switches etc. repeatedly.

- Repeatedly putting clothes on, and then taking them off.

- Counting over and over to a certain number.

- Touching certain objects in a specific way.

- Repeating certain actions, such as going through a doorway.

- Constantly seeking approval (especially children)

Fear of contamination and washing and cleaning compulsions:

It is the most common obsession. The person feels contaminated and dirty even on carrying out routine chores such as handling door knobs, picking up fallen objects, using money handled by others or just passing by a garbage can. These fears and rituals are of extreme nature – the washing may consume many hours and may leave the hands raw. Also, they may spend hours keeping the house clean, or clean the bathroom repeatedly before taking a bath.

There are some who fear that the dirt and germs brought in by themselves or others would spread and cause harm to others. Hence, they avoid touching others till they have a bath or clean up the whole house after someone visits. The washing sometimes become highly ritualized such as scrubbing the hands in one particular way or bathing in a particular order.

Doubting and checking:

Persons with these obsessions have repeated doubts that something bad will happen because they have failed to check something thoroughly or completely. Their need to check repeatedly is driven by the possibility that something terrible will happen even though they recognize that the possibility is an extremely remote one. For example, they doubt that the gas knob is not turned off properly and as a result gas will leak and result in a fire accident. Common examples are, repeated checking of door locks, gas knobs, and electric appliances. Other common examples include, counting currency notes repeatedly, and going over a file or homework assignment (in the case of children) repeatedly to check for any possible errors. However, even after spending considerable time in checking they are rarely satisfied. Sometimes, they may seek reassurance from others to ensure that they have not committed any mistake that may prove to be dangerous. For a casual observer, they may appear very slow and inefficient, particularly at work. Children with checking compulsions are often seen as poor learners at school and may fall behind in studies.

Need for symmetry and ordering / arranging:

Persons with these obsessions are usually seen as those who like to keep everything neat and tidy. But the need to be tidy would be a major preoccupation and take priority over carrying out other routine activities. They may spend hours arranging the table for a meal or making a bed till satisfied that everything is in the right place.

Sexual and aggressive obsessions:

People with these obsessions have repeated thoughts or images of a sexual or aggressive nature. For example, sexual obsessions could be in the form of intrusive sexual images of family members and gods and goddesses. Aggressive obsessions are usually about urges to harm loved ones, usually family members. Persons suffering from sexual and aggressive obsessions suffer from intense guilt and anxiety.

Counting and repeating compulsions, hoarding and ruminations are other common clinical presentations of OCD.

CAUSES OF OCD

The exact cause of OCD is still unknown. However, there are many theories of causation of OCD. These are broadly classified into biological and psychological theories.

Biological theories:

At this stage, it is fairly clear that OCD has a biological basis and is caused by certain biochemical changes occurring in the brain. These changes involve neurotransmitters which are chemicals in the brain. A neurotransmitter called serotonin is said to be deficient in the brains of individuals suffering from OCD. Drugs which increase the concentration of serotonin in the brain reduce the symptoms of OCD.

Further evidence that OCD is a disorder of biological origin comes from its association with some neurological disorders. Individuals with encephalitis, tic disorders and chorea are more likely to develop OCD. Brain Imaging consistently shows abnormalities in frontal cortex, basal ganglia and cingulum

It is now believed that OCD is a heritable disorder in some patients. About 3-7% of first degree relatives (parents, siblings and children) of individuals suffering from OCD have similar illness. OCD is also genetically related to a neurological disorder called ‘Tourette disorder’. The relatives of individuals suffering from OCD have, not only a higher propensity to develop OCD, but also Tourette disorder. It should, however, be noted that OCD is a heritable disorder in only a minority of individuals.

Role of stress:

Stress of any kind, by itself, does not cause OCD, but can precipitate the onset of OCD in vulnerable individuals. But, stress is well known to worsen pre-existing symptoms. The common precipitating stressful life events include separation from loved ones, major life changes such as loss of a job, problems at work, pregnancy, childbirth, and abortion.

Role of personality:

There are some individuals who are very perfectionistic, rigid and meticulous in what they do. They are excessively preoccupied with order, precision, rules and organization. These individuals are said to suffer from obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, but not from OCD. It was earlier believed that this type of personality predisposes one to develop OCD. However, it is now clear that the presence of this personality disorder need not predispose an individual to develop OCD. In fact, most patients with OCD do not have obsessive-compulsive personality. On the contrary, individuals with low self-esteem, who are easily hurt by criticism, and who display anxiety in interacting with others and in participating in social situations such as parties and marriages are comparatively more likely to have OCD.

Psychological theories:

For many years psychiatrists believed that OCD developed in individuals who had been brought up by rigid and strict parents. It is now clear that such is not the case and those psychological conflicts and deep-rooted problems of early childhood do not cause OCD.

Learning theory explains about how obsessions are maintained.

Course and outcome of OCD

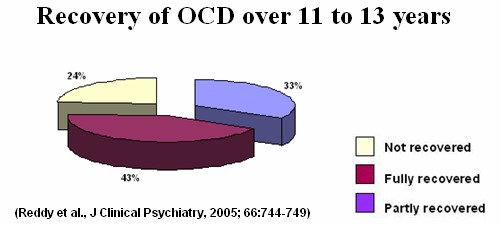

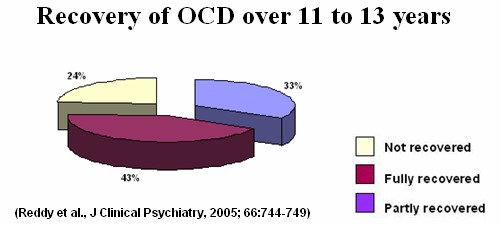

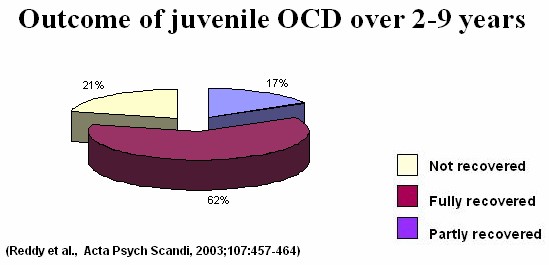

It has often been stated that OCD is a chronic illness and that few patients recover from it. However, research by several OCD specialists suggests that this is not the case, and that a good proportion of patients with OCD recover well. Here are some of the findings of two studies done at NIMHANS to study the long-term outcome of patients being treated by us for OCD.

OCD in children and adolescents

OCD was once thought to be rare in children and adolescents. This is because its manifestations in childhood may be subtle and difficult to recognize, and also because OCD symptoms may be confused with normal behaviours and superstitions that are a part of childhood, such as “lucky numbers” or bedtime rituals. However, we now know that up to half of adult OCD patients may have experienced their first symptoms in childhood and adolescents. Studies done in India as well as around the world suggest that it may affect 1-4% of children. Symptoms may begin in early childhood (around 6-7 years) or in adolescence, and are commoner in boys than in girls.

OCD is diagnosed in children using the same methods as in adults. The important differences are that:

- Children may not find their behaviours unreasonable, whereas most adults will usually acknowledge that their symptoms are irrational.

- Children may not be able to express the exact nature of their thoughts and fears. Sometimes, they may say that they perform compulsions until they feel “just right” or “satisfied”, rather than to diminish anxiety or distress, or describe a vague sensation that “something bad” will happen if they do not carry out their compulsive behaviours.

Common symptoms in childhood OCD are similar to those in adults, and include obsessions related to contamination, aggressive themes, a need for symmetry and exactness, and sexual and blasphemous thoughts, and compulsive washing, repeating, ordering, counting It is important to note, though, that up to one-third of children may have “miscellaneous” obsessions and compulsions that do not fit into these categories. Children often may not report these symptoms and may try to conceal them, as they find them embarrassing. Often, the first indicator of OCD may be slowness, pending excessive time in routine activities, avoiding certain situations, social withdrawal, or difficulties in academics. Children with these symptoms should be evaluated to identify OCD, as well as to differentiate it from conditions such as depression, anxiety or learning disability.

It was previously believed that OCD in children was a severe form of the illness, and that most children did not recover. However, research done at NIMHANS and elsewhere suggests that this is not the case.

Treatment of childhood OCD is almost similar to adult OCD. Both medications and behavior therapy are effective, and are described in detail below.

Drug treatment of OCD

Selective Serotonin Re-uptake Inhibitors are used in treatment of OCD. There are various chemicals or neurotransmitters in the brain, and serotonin is one of them. These drugs act to increase the amount of serotonin available for the nervous cells in the brain. This corresponds to the known serotonergic hypothesis for the etiology of OCD (See the section on Etiology). The oldest member of this group is clomipramine. More recent additions to this group, and more selective in their mechanism of action, include fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram and escitalopram.

These drugs also belong to the larger category of drugs called anti-depressants. There has for a long time been some controversy whether these drugs treat depression or OCD. However, the consensus opinion at this point of time is that although they have potent actions on depression, they also have independent anti-obsessional properties. So whether you are depressed or not, and in spite of the broader classification of these drugs, these drugs will work for you, if you have OCD. These medications are also useful in treating a number of disorders that can co-occur with OCD. These include hypochondriasis, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and premature ejaculation.

There is some evidence that clomipramine may be slightly more effective than other medications; however, because of its higher likelihood of side effects, it is usually used when at least one other medication has not been effective.

Sometimes augmenting agents are used to increase the effectivity of the above mentioned agents. Rarely other modalities are recommended in resistant cases. Contact your doctor for more information

Behavior Therapy for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

What is behavior therapy?

Behavior therapy comprises of a variety of techniques used to modify or replace maladaptive behaviors with more adaptive behaviors. Obsessions and compulsions seen in OCD are examples of maladaptive behaviors.

In treating OCD several behavior therapy techniques are used. Of them, “Exposure and Response Prevention”, is the most effective and widely used technique. It is effective in 60-70% of patients suffering from OCD.

The rationale behind Behavior Therapy:

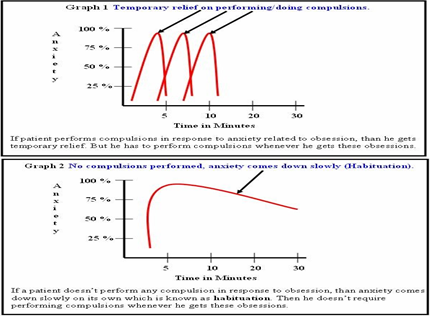

We know that most patients suffer from both obsessions and compulsions. Compulsions are performed to reduce the anxiety or discomfort associated with obsessions. Because the compulsions succeed, even if momentarily, in reducing anxiety, the compulsions are reinforced and are more likely to occur again in response to obsessions or certain situations which trigger obsessions. In the due course of time, for most patients, the compulsions which were originally employed to reduce the distress, themselves become a source of great discomfort. To put it simply, the obsessions lead to compulsions, and because the compulsions reduce the anxiety due to obsessions, they tend to persist establishing a vicious cycle difficult to break.

The “Exposure and Response prevention” technique based on the principle of “habituation” of emotions breaks this vicious cycle. What then is habituation? It is based on a simple principle that irrational fears and behavior disappear upon repeated exposure to the sources of fear and anxiety. By repeated and prolonged exposure, the individual gets habituated or used to the anxiety or discomfort to the point where the sources of fear lose their ability to provoke any anxiety, fear or discomfort. However, patients with OCD tend to handle their fear and anxiety by indulging in compulsions and active avoidance of all those situations that could trigger obsessions. On the contrary, in behavior therapy, patient is encouraged to gradually expose oneself to the anxiety-provoking situations and get habituated to the discomfort. And also, the patient is encouraged to not avoid any situations and indulge in compulsions. By preventing oneself from performing compulsions, the anxiety associated with obsession gradually dies on its own. Once the patient get used to anxiety the obsessions and compulsions also gradually disappear.

Take for example, the patient who washes hands repeatedly whenever he touches doorknobs because of the fear of contamination. In behavior therapy, the patient is encouraged to touch the door-knobs but prevented from hand washing .By doing so. The patient’s

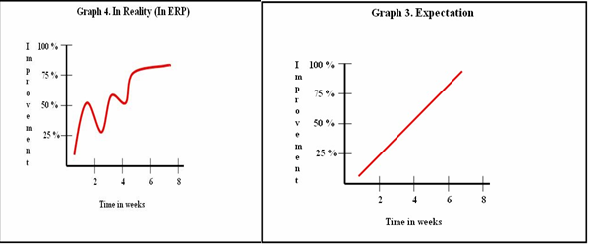

anxiety shoots up but gradually comes down on its own and the patient gets used to it. On the other hand, if the patient indulges in hand washing. Anxiety drops down quickly not allowing the person to get used to it. Result, his or her fear of contamination persists and the person has to indulge in time consuming and distressing compulsions to get rid of the fear of contamination (Graph – 1). The only way then to break this vicious cycle is to expose but not to wash hands. By such repeated exposures, the fear of contamination gradually disappears and hence the compulsion of hand-washing also (Graph – 2)

It is important to understand at the outset, that the treatment causes discomfort and that one should be prepared to go through some discomfort to obtain relief ultimately. The speed of habituation of emotional responses varies from person to person. Some may require lesser time (e.g. 30 min) of exposure while others may require repeated long exposures (1-2 hours) before any diminution of the anxiety occurs. Usually the compulsions and rituals are the first to respond and the obsessions take longer to “wear out”. Most show response between 10-12 hours of exposure and response prevention. For a successful outcome, motivation to get well and withstand the discomfort in initial sessions is vital.

The role of family in the treatment of OCD

The cooperation and support from the family often play a vital role in the treatment of OCD. OCD rarely leaves the family system unaffected. Marital discord, divorce and separation are common results of the stress that OCD puts on family members. Some families blame themselves for their child or spouse’s illness. Family’s sense of guilt and shame may be further reinforced by the advice from friends and relatives who often tell them that the patient is “not ill, just going through a bad phase”, and more discipline and attention is the solution to the patient’s problems. The family is often uncertain whether the rituals are part of an illness or willful behaviors for attention and control. Family responses to OCD are of three patterns: the accommodating, antagonistic and split family.

Accommodating families are usually overinvolved, permissive, and intrusive in relating to the patient. Family members often join in and help in patient’s rituals to reduce tension in the family. This is not only counterproductive for the patient but also creates tension in the family. On the other hand, antagonistic families refuse to involve themselves in patient’s problems. They are rigid, detached, hostile, critical and punitive. Anger, conflict among family members and on occasion’s physical violence are common in such families. In the split family, some are overinvolved and the others are critical, hostile and uninvolved. It is clear that these three commonly seen family responses to OCD are not conducive for recovery and treatment of OCD. Hence, the involvement of family members in the treatment of OCD is necessary, particularly in the implementation of behavior therapy and monitoring of drug administration.

Patient and a family member (who can be a co-therapist in ERP) can learn about principles and techniques of ERP. Family members can assist the patient in graded exposure and response prevention. This would help outpatient ERP that can be practiced at home. Family members should be aware that unrealistic expectation (as illustrated in Graph 3) might result in disillusionment and poor adherence to therapy. On the other hand, improvement occurs in a slow fluctuating manner (as illustrated in Graph 4) and this realization would help families appreciate the gains that occur over the course of therapy.